Lately I've been following posts by the Old Urbanist and one of his main inspirations, Nathan Lewis. Lewis puts aside political issues of compromise with car boosters and examines the question of how we would want our environment to look if we weren't planning for cars. He looks at pedestrian-oriented cities around the world and highlights examples of good design. One concept he refers to again and again is the Really Narrow Street.

These streets were usually created before cars were invented, and they have no place for cars. Some are too narrow for any car. Most are wide enough for one car to pass, but not much wider. There are examples from every continent, including Europe, Africa, Asia and South America.

In North America we have a few of these streets in some of our older towns. Here is one of the oldest, Acoma (established ca. 1300):

Here is Santo Domingo (1496):

Quebec (1608):

Boston (1630):

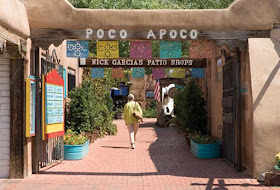

Albuquerque (1706):

One of my favorites, in part because it's a small town, is Rockport, Massachussetts (1743):

I spent an enjoyable few days in Rockport last summer. The street in this picture, Bearskin Neck, leads to the main docks and was a key route during the town's heyday as a fishing port. It now leads to the departure docks for some tourist boats, but is more of a destination in itself, and is lined with shops and restaurants. It functions essentially as a woonerf.

Notice that none of the streets above were laid out after 1800. Lewis attributes this to an American fad he calls "nineteenth-century hypertrophism," where wide streets became a symbol of progress and wealth. He observes that in his hometown of New Berlin, New York, the main street was designed so that you could turn a horse and carriage around in it, even though that wasn't necessary for any social purpose.

Lewis argues that Really Narrow Streets privilege the pedestrian and create an opportunity for intense commerce that cannot be matched by any street wide enough to handle cars and pedestrians together. This is an experience that shopping malls, cruise ships and theme parks are designed to replicate.

At this point you may be saying to yourself, "We tried pedestrian streets in the seventies, and many cities are allowing cars back in, because it killed the street." One answer to that is that the streets were still "hypertrophic," too wide to feel comfortable with just pedestrians. My main answer is that it was the subsidies to sprawl commerce that killed downtown streets. Many of them would probably have done just fine as pedestrian streets if the government hadn't been simultaneously building big competing highways and parking lots on the edge of town. Some of them have done fine.

The horse&carriage U-turn issue can't be the only thing. I suspect our forefathers had enough traumatic experiences with fire that they deemed the larger house separations a major benefit.

ReplyDeleteBTW, you should really go visit Provincetown while you're at it.

ReplyDeleteA good example is North America's largest urban car-free zone on the Toronto Islands. The 600 residents and businesses have narrow streets and see no need for any traffic control devices.

ReplyDeleteThe waiting list to live there is currently about 20 years (yes, that's years!) long.

Alternatively, we have the examples of Steamboat Springs and Colorado Springs where the streets are wide enough to turn a 12-horse stagecoach around.

ReplyDeleteFire standards are absolutely the key. You must have 20-feet (34-feet with parking) unless you are willing to install a whole slew of stand-pipes and sprinklers.

http://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/coffee-break/cb_fp_2009_1.pdf

(USDHS/FEMA regulates street widths now? Who knew?)

Narrow streets only go pedestrian/cycle friendly if you can close them to cars, otherwise motor vehicles occupy it too. Look at the Bristol traffic Montpelier coverage to see this -anyone on foot is forced into a road where they have to argue with oncoming vehicles about right of way

ReplyDeletehttp://bristolcars.blogspot.com/search/label/montpelier

Pre-1900 Fort Collins was planned with 60' wide curb-to-curb streets in order to turn a horse carriage around. Now, why exactly you need to turn it around right there instead of just circling the block is truly beyond me.

ReplyDeleteI've been wondering about the ultra-wide streets from the 1800s and early 1900s. Can you direct us to any references discussing that trend?

ReplyDeleteCan't forget Baltimore (1729), Philadelphia (1682), and New York City south of 14th Street (1624). The oldest neighborhoods in our great mid-Atlantic cities have narrow streets in their oldest sections too.

ReplyDeleteWe don't have narrow streets in D.C. because L'Enfant planned for wide streets.

Check out the Little Italy in Baltimore or some of the named streets/alleys in Old City in Philadelphia for some good examples of streets that are too narrow for two cars.

You actually don't have to close streets to cars to make them pedestrian/bike friendly, but only if they're "really narrow" to start with. A street that's 15-20 feet from building to building is narrow enough to tame the cars (which must be restricted to one-way travel), but since it leads to such a dense environment with little room for much parking, there's not much vehicular traffic anyway. Pedestrians and cyclists can rule the streets and cars just have to deal with it. Nathan Lewis provides many great examples, a lot from Japan on his site. Peruse the archives, there's a ton of great articles that are beautifully illustrated.

ReplyDeleteAlso, one thing that is little researched is just where this "hypertrophic" pattern came about. Nathan Lewis attributes this to an aesthetic of "heroic materialism", which basically means celebrating the huge and the mass-produced. It's an industrial revolution aesthetic, but it's just an aesthetic. The functionality of it, i.e. being able to turn a carriage around, seems more like post-rationalization. Firefighting rationalization, which is more of a modern day accommodation to our massively oversized firetrucks isn't a reason in the past either, since building were still directly connected side-to-side. The relatively wide streets of Chicago and San Francisco didn't prevent massive fires from crossing the street anyway. It's more of a "bigger is better" thing, yet nobody put together just how dysfunctional it has made our cities.

You know something? There's nothing dysfunctional about Manhattan north of 14th Street that doesn't also apply to Manhattan south of 14th Street. Lewis has been trying to rationalize social hatred of the cities in terms of their urban form (a rationalization that partly goes back to Jane Jacobs, though to her credit she partly knew when to stop, and to James Kunstler, who does not). It doesn't stand up to any global scrutiny. The neighborhood with the Really Narrow Streets in Tel Aviv is the city's worst. People in the city would consider 60' streets wide and 40' streets normal, but the medieval urban form they'd associate with slums.

ReplyDelete> There's nothing dysfunctional about Manhattan north of 14th Street that doesn't also apply to Manhattan south of 14th Street.

ReplyDeletePoppycock. I'm in Manhattan below 14th almost every day of the week. As far as streets go, it is my "normal". On the occasion that I travel uptown I have to quickly reacquaint myself with unbridled aggression of motorists on wider, less congested streets. The difference is stark and the observation of it is commonplace.

I don't care which urban thinker is allegedly trying to rationalize what hatred; I prefer narrower streets because they are less mortally terrifying. It's not complicated.

I was in Manhattan every day north of 14th and occasionally south of 14th for five years. I grew up in Tel Aviv's Old North, where streets are the same width as in the Village. And I frequently visit Monaco, whose streets go down to 20'. And I don't see any difference in driver aggression or pedestrian-friendliness. (Actually, New York is more ped-friendly than Tel Aviv and Monaco, since its streets have sidewalks and are not road-engineered to death.) Don't automatically assume everyone has the same visceral reaction to cities you do.

ReplyDeleteThe issue surrounding Lewis's own writings on cities is a little different. Not only does he assume that everyone perceives cities the same way he does, but also he tries to analyze all of urban history through the same prism. To hear him and to some extent Charlie Gardner tell it, if only American cities had built narrower streets, the urban patricians would not have wanted to demolish urban neighborhoods in favor of urban renewal.

Part of the problem is that we ARE sourcing from Nathan Lewis and Charlie Gardner. All Lewis offers is a vision and total contempt for others who try to figure out the compromises needed to bring the vision into reality. (Hardly healthy.) Gardner is much better about this, but a key element of the "Old Urbanism" they espouse is the aesthetic element.

ReplyDeleteWork by others, such as Mathieu Hélie, offers a much more sophisticated theoretical picture of how such environments came to arise. This school of thought looks at how urban forms arise in the absence of any contrary voice (e.g. land use regulation).

Thanks for picking up this topic.

ReplyDelete@Alon: I've tried to avoid as best I can that sort of form-based determinism, and in my discussions of narrow streets I've intended to focus on the benefits in terms of connectivity, commercial street frontage, urban variety, etc. They are simply one important ingredient in considering the configuration of the street network, and one which Nathan (and I) noticed had received scant attention even within the New Urbanism.

As to the reasons for the adoption of wide streets, I think Jeffrey is right that the u-turn explanation is a bit post-hoc, an attempt to rationalize a decision which otherwise seemed inexplicable. The Commissioners who laid out the Manhattan grid, at least, were very concerned with the perceived flaws of narrow streets, some of which were pseudoscientific (narrow streets bred disease, or impeded "the circulation of air") while others (the firebreak concern) were disproven later as Jeffrey mentions. London in contrast reacted post-1666 by encouraging brick construction and developing firefighting services rather than widening streets, though not for lack of trying.

Small streets are part of what makes a city. Here in Melbourne (Australia) the city's laneways are typically featured rather than hidden when talking about/ marketing the city. Visitors to the CBD are rarely advised to go to wide Latrobe St but instead explore the city grid, with laneways, alleys like Degraves St (http://g.co/maps/627zz). The one-way streets in the grid are narrow too (rather than very narrow), typically the width of two cars (one parked/one through) with decent footpaths and portions of them are scheduled closed during the day to vehicles - way too many pedestrians!

ReplyDeleteWide streets keep you away from the effluvia of the horse drawn vehicles. That you could make a U-turn on one that wide was a side effect.

ReplyDeleteMarc, I think there are two separate issues here. One is how much activity there is on the street, and how accessible it is by public transportation. Times Square is very wide, but because it's served by multiple subway lines and has all-day commercial and entertainment business, it's amply used. In contrast, there are fewer people at Herald Square, and yet fewer on the pedestrianized lanes on Broadway in the 50s. You can go even wider than Times Square: Shanghai's pedestrianized Nanjing Road is very busy, since it's located on top of the city's busiest subway station and is flanked by many multi-story urban shopping malls on both sides.

ReplyDeleteWidth is a separate issue. It's easier to pedestrianize when the street is narrower than when it's wider - in other words, the level of required activity is lower. If there are too few people relative to street width, then it feels desolate, as if something is missing from it. Lower Manhattan would be much easier to pedestrianize as a result.