The Department of City Planning

thinks it would be a good idea to have a bus terminal in the new "Flushing West" district that they're planning (

PDF). Apparently at one of their outreach sessions people talked to them about "Rerouting of bus routes to alleviate traffic on Main Street" and the "Need for a distinct central bus terminal." So they said they would "Evaluate siting a mixed-use Bus Transit Center (BTC) near northern and southern edges of the rezoning area."

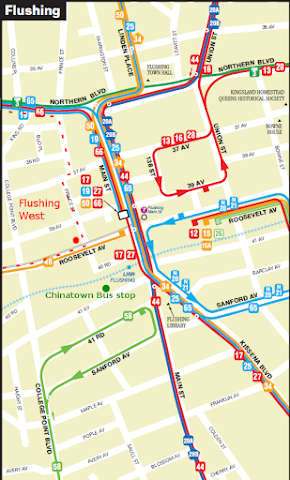

As this map shows, there are twenty MTA bus lines that converge on Flushing, as well as the #7 subway, the Port Washington Branch of the Long Island Rail Road, and private buses to Chinatown and Sunset Park. There are also private buses to various casinos in the region. Of these, the underground 7 train station is the only one that is at all protected from rain or snow. The buses pick up and drop off at a variety of stops along Main Street, 39th Avenue, Roosevelt Avenue, 41st Avenue and 41st Road.

Because the Flushing West district starts at Prince Street, a block west of the western entrance to the Main Street subway station, the proposed bus station could be as close as the corner of Roosevelt and Prince, 225 yards from the subway, or as far away as Northern Boulevard and the river, three quarters of a mile from the subway.

But is there actually even a need for a distinct central bus terminal? It's a good idea to go over the reasons we have them. City Planning gave only one: "Provide relief to bus congestion from curbside layovers in the downtown." But if we think about existing bus terminals like the Port Authority or Newark Penn Station, they provide value in several ways:

- One-stop shopping for buses. Right now if you're going to Bay Terrace, you can take either the Q13 or the Q28, which is handy because they leave from roughly the same spot in Flushing. But if you're going to Northern Boulevard in Bayside you'll have to decide ahead of time whether you're taking the Q12 or the Q13, because they leave from stops a block apart.

- Easy transfer between buses, and from buses to trains. Right now if you want to change from a northbound Q44 to an eastbound Q13, or from the 7 train to a southbound Q17, you have to walk a couple of blocks on crowded sidewalks.

- Short-term bus layovers. Some of the bus routes (like the Q44) pass through Flushing, but most of them terminate there. It makes sense to start and end as many bus driver shifts as possible at transit hubs, because it encourages drivers to commute by transit. Sometimes drivers need a short break between runs, and sometimes they finish a run early. It's important to have enough short-term bus storage to handle those needs.

- Long-term bus layovers. Demand is not flat for buses; there are rush hours. It is often more efficient to store buses close to the transit hub in the middle of the day instead of sending them to the depot (a two mile trip) and back.

- Avoiding street congestion. One of the biggest time savers for bus riders at the Port Authority is that most of the buses have direct ramps into and out of the Lincoln Tunnel, and don't have to compete with private cars.

- Ticketing, shelter, bathrooms, food and shopping for people waiting for buses.

The first thing to ask is what the current arrangement does and doesn't provide. It does not avoid much street congestion or provide for long-term layovers. According to the City Planning powerpoint, the buses stored for short-term layovers get in the way of buses picking up and dropping off passengers. As I detailed above, some of the transfers require walking multiple blocks through dense crowds, and there are a few problems with one-stop shopping. There is very little shelter for people waiting for buses.

On the plus side, transfers from the 7 train to most of the buses are pretty quick and easy. One-stop shopping for the buses that go on Main Street, Kissena Boulevard and Parsons Boulevard works pretty well, and now that bus schedules are available through Google Maps it's even easier to know which bus is scheduled to leave next. There are public bathrooms and Metrocard machines in the subway station. Downtown Flushing's biggest advantage is in terms of food and shopping. If you're transferring in a hurry you can usually pick up a scallion pancake, a Big Mac, a bubble tea or any of a staggering variety of other fast foods and beverages before the next bus leaves. Within a block of the Main Street station there's a Macy's, a Duane Reade and half a dozen Chinese mini-malls.

So what would the proposed bus terminal provide that we don't already have? Shelter and space for short-term layovers, maybe shorten a couple of the transfers and make one-stop shopping a bit easier. Hmmm, maybe that would be worth it if someone else paid for it...

But note that the terminal proposal doesn't do anything to address the biggest obstacle to bus flow: private cars. And it would make the single most important transfer - the transfer from the 7 train to any bus - at least a block long, and potentially much longer. People currently disperse from the corner of Main and Roosevelt in all four directions to board buses using six staircases and two escalators; the proposal would concentrate them all along one route, accessed by one staircase: the one at the northwest corner.

Some people go to Flushing specifically for the restaurants. Others go for specific shopping and cultural anchors, and stop at restaurants on their way. But if you think about it for a minute, it's clear that the dispersed pedestrian flow from the subway to the bus stops is one of the biggest drivers of business at the shops and restaurants in the area.

There are of course other factors at play, but I wonder how much of the affluence and growth of Downtown Flushing relative to other transit hubs like Jamaica and Journal Square can be credited to this layout, where businesses are on the way in a sense that can't be said of the other hubs. How many people would cease to walk by the Quickly+ on Roosevelt if the B12 terminus were moved west of Main Street? Are the Flushing merchants ready to find out?

Sadly, I'm guessing that they are. That first quote from the City Planning powerpoint, "Rerouting of bus routes to alleviate traffic on Main Street," sounds just like the kinds of quotes that Flushing's elites give to papers. No matter how clear the evidence that the vast majority of shoppers arrive by bus or train, both the old white elites and the new Asian elites seem utterly convinced that anyone who matters comes by car.

Despite what livable streets advocates, city planners and the developers themselves wanted, these merchants and politicians insisted on raising the amount of parking in the new Flushing Commons development to an insane level. They fought bitterly a recent attempt to increase bus speeds through the area by dedicating lanes of Main Street to buses (

PDF). The new mall south of Roosevelt Avenue comes with a staggering amount of parking.

It would not surprise me at all if it were a merchant or politician who asked for "Rerouting of bus routes to alleviate traffic on Main Street." This is clearly someone who sees the upper-middle-class white and East Asian drivers as the rightful users of Main Street, and the bus riders, many of them black and South Asian, as interlopers who must be banished to the periphery.

This is yet another situation where we have to ask "

who's getting out of the way?" The only way that I could see a bus terminal as an improvement is if it (a) directly connected to the subway and (b) bypassed a large amount of car traffic. No long nasty tunnel like the one to the Port Authority; I'm talking about demolishing a big chunk of one of the blocks at the corner of Main and Roosevelt. I'm talking about bus-only underground ramps from further out on Main, Kissena, Parsons and Northern that flow right into the bus bays and layover garage.

Of course, that would be a humongous cost, and if you're going to dig a tunnel you might as well put in an orbital subway connecting Flushing to Jamaica, the airports, Astoria and Upper Manhattan. None of it sounds like it would justify the cost of construction, so let's drop that, at least for a few decades.

What could we do that's cheaper? In 2012 the Department of Transportation considered reconfiguring Main and Union Streets to provide dedicated bus lanes, and rejected those options because they didn't want to slow down private cars and trucks (

PDF). If we really want to improve bus service, we could revisit those options. We could also widen the sidewalks on Main Street to make room for bus shelters.

What we should not do under any circumstances is move bus stops away from Main Street and into the Flushing West area. Transit advocates need to be clear: that is not a bus proposal, it's an anti-bus proposal. The staff at City Planning listened to the anti-bus people; now they need to listen to the pro-bus people and kill any effort to put a bus terminal in Flushing West.