Alexander asked on Twitter about the series of posts I did on farebox recovery ratios reported to the United States National Transit Database from 2007 through 2010. The Federal Transit Administration has continued to publish the NTD every year; I just got a little tired of compiling the data, and engagement kind of went down. But let's take a look and see how things are these days!

The Database for each year used to be published in December of the following year, so 2021 is now the most recent year available. The data used to be in Table 26, but the FTA staff is no longer numbering the tables, so now it's in the Metrics table. I've imported the 2021 Metrics table into Google Sheets for your convenience.

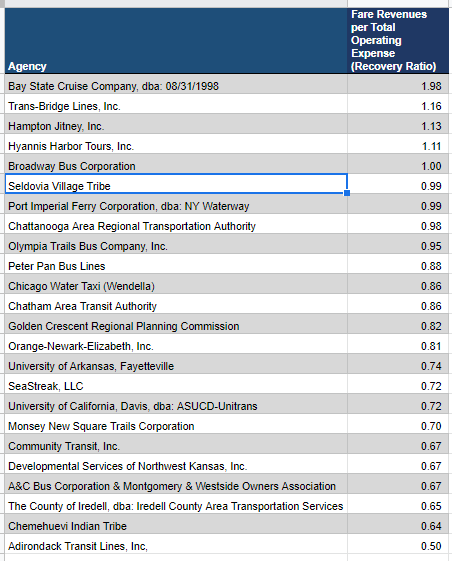

Since we're looking at traditional transit providers, the first thing to do is filter out the contract providers (any TOS but DO) and the demand response and vanpool providers (Mode of DR and VP). That leaves us with 22 transit providers.

The first thing I noticed is how many more ferry operators are reporting. In 2010 we had New York Waterway and BillyBey, but in 2021 we have eight: Bay State (Boston to Provincetown), Hyannis Harbor (also Cape Cod), Seldovia Village (connects Homer, Alaska to a Native village with no competing roads), New York Waterway, Chicago Water Taxi, Chatham Area Transit (connecting downtown Savannah to the Convention Center), SeaStreak (connects New York with bedroom and resort towns in New Jersey and Massachusetts) and the Chemehuevi Indian Tribe (connects one end of London Bridge to a casino across Lake Havasu).

In 2010 we had the University of Georgia; in 2021 we have the University of Arkansas and the University of California at Davis. Those don't really count because they're paid for up front by student fees. The Chattanooga inclined plane also broke even in 2021.

A couple of items were flagged by the FTA staff as "Questionable," including the claim by the Golden Crescent Regional Planning Commission that its bus service brings in $9.26 per trip in fares, when their website says they only charge $1.50. They didn't flag the Developmental Services of Northwest Kansas's claim that they earn $16 per trip in fares while only charging $3, but I find that questionable myself. Similarly with Iredell County Area Transportation Services' report of $7.75 per trip contrasts with their website's $1-3 fare. I'm guessing both of those are clerical errors.

That leaves nine bus companies, all in the New York area, making more than a 50% farebox recovery ratio in 2021, which you may remember was a difficult year for transit agencies: Trans-Bridge, Hampton Jitney, Broadway Bus, Olympia Trails, Peter Pan, Orange-Newark-Elizabeth, Monsey New Square Trails, Community Transit, A&C Bus/Montgomery and Westside, and Adirondack Transit.

To answer Alexander's question: there are six bus companies on this list that use the Lincoln Tunnel Exclusive Bus Lane: Trans-Bridge, Olympia Trails (the CoachUSA subsidiary serving Newark Airport from Manhattan), Peter Pan, Monsey New Square Trails (a commuter service focused on Hasidic Jews), Community Transit (a CoachUSA subsidiary serving East and West Orange and Livingston, NJ from the Port Authority) and Adirondack Transit. Of the buses making more than 75% farebox recovery ratio in 2010, some had gone out of business before the adoption of work-from-home arrangements when doctors began discovering COVID-19 cases in March, like Frank Martz Trailways.

Most of the companies missing from the short list were just losing a lot of money. Suburban Transit, the CoachUSA subsidiary serving New Brunswick area, made a 22% farebox recovery ratio in 2021. DeCamp made 21%, and Rockland Coaches, the CoachUSA subsidiary formerly doing business as Red and Tan Lines, made 19%. This is a useful lesson, because the management of these companies took a very conservative approach, canceling all service for months and leading restoration with peak-direction rush-hour service. Rockland has still not restored full-day or weekend service. In contrast, Trans-Bridge, Olympia Trails, Peter Pan, Monsey and Adirondack all run service middays, reverse-peak and weekends.

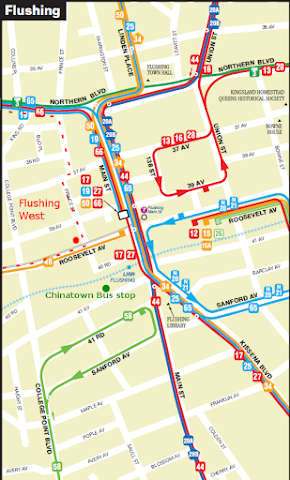

It wasn't flagged as "Questionable," but I find it questionable that Broadway Bus was able to run eight buses for $13.97 an hour total. If I'm not mistaken, Broadway Bus and A&C may have gone out of business since 2021. With three routes in Newark I don't quite understand how Orange-Newark-Elizabeth (a CoachUSA subsidiary) makes an 81% farebox recovery ratio.

The big success story in this list, of course, is Hampton Jitney, which made a 13% profit in 2021. The Hamptons were infamous as the destination for a number of wealthy people who (with no good reason) "fled the city." They did, of course, have to come back at least temporarily, and while they may be willing to drive out there, spending hours on the Long Island Expressway is a different story. So those who can't afford helicopters take the train or the bus.