In recent posts I’ve talked about how transit needs dedicated lanes, and how on a hundred foot avenue you don’t want to take a lane away from parking. The Department of Transportation seems to have figured this out, but there are serious problems with the approach they’ve been taking lately: offset lanes.

Last winter, Joby Jacob and I took the B46 Select Bus Service down Utica Avenue. I was struck by how slowly the bus moved, even in the sections that supposedly had dedicated bus lanes. It was pretty clear why: on many blocks there was a car or truck in the bus lane, sometimes more than one.

Sometimes all the curbside parking spaces were taken by parked cars, and the blocking car was double parked. It takes some spectacular chutzpah to think that your personal need to pick up an egg sandwich is pressing enough to keep a hundred people waiting. But as Donald Shoup has shown us, the underlying problem is that the City doesn’t price parking properly. If it cost more to park on these blocks people would park elsewhere, or for shorter periods of time, or even take transit. That would free up space for these short-term stops.

Sometimes there is space at the curb, but the drivers don’t pull all the way in to the space. This is occasionally understandable if the space is narrow enough that it would take a lot of time to parallel park. A lot of the time, however, there is plenty of room to pull in to the curb. The only explanation I can see for this behavior is that the driver is trying to signal to the police that they understand they’ve pulled into a no-parking zone (bus stop, fire hydrant) and will be leaving as soon as possible. It’s still a hugely selfish move, because it forces an entire bus full of people to wait for a gap in the next lane over to go around.

It doesn’t help that the DOT has debased the value of red paint by using it for part-time bus lanes, letting people get in the habit of unloading trucks and parking cars in red lanes, teaching them that the paint doesn’t really mean “don’t put your private vehicle here!” And the NYPD doesn't seem to be all that effective in keeping the lanes free.

So if we can’t put the transit lane at the curb, and we can’t offset it one lane, what should we do? Stay tuned...

Here are some reasons to get people to shift from cars to transit:

Friday, November 17, 2017

Saturday, October 21, 2017

Local knowledge, global bullshit

In my neighborhood, on a narrow block zoned M-1 next to the Long Island Railroad main line, is a parking lot. A few years ago, the owners of the building across the street put forward a plan: the City would rezone the block for residential, and they would build a ten-story apartment building. The City Council member for this district said he had concerns but wanted to hear more.

After a few contentious meetings, stories emerged in the news and on Facebook, and were eventually published in a change.org petition and a website: the rents would be sky-high, the new building would be massive and out of context, and it would dump hundreds of new riders on the already overcrowded elevated train and neighborhood schools. The street was not adequate to handle the traffic. The entire community was against it. Eventually the City Council member declared that he was against the project, and it was dropped.

Last week I heard someone on a podcast talking about the value of local knowledge in city planning, crediting Jane Jacobs for it. Certainly, Jacobs catalogs a number of clear cases where planners came into an area with little or no knowledge of it, and royally messed it up. She might have declared the defeat of this project to be a triumph of local knowledge.

The problem is that all the stories I listed above were false. The existing building is run by a nonprofit specifically dedicated to providing affordable housing, and their plans for the site specified that the vast majority of the rents would be below market. The existing building, built in 1931, is a superblock with 472 units. Less than a block away are two more complexes with over 400 units each. Two blocks away is a row of four twelve-story towers-in-a-parking lot on top of a hill. This building would fit in completely with the existing context.

The impacts on transit are similarly overstated. First of all, some people won’t be commuting to Manhattan anyway. They could be retired, or telecommuting, or working elsewhere. And unfortunately, some won’t be commuting by train. In 2008, Rachel Weinberger wrote a great report called “Guaranteed Parking, Guaranteed Driving,” demonstrating that if you include parking with housing, people are much more likely to drive. The plans called for 220 units in the new building, and about as many parking spaces, which sounds dreadful. Based on Weinberger’s research we can predict that those 220 spaces would induce a lot of driving.

Of course some people will take the train no matter what happens, and that number will probably increase as more people realize that driving is a pain in the ass. So let’s imagine that these 220 apartments produce a really high number of transit commuters to Manhattan, say 330, or an average of 1.5 commuters per apartment, including two-bedrooms, one-bedrooms and studios. According to the MTA, on the average weekday in 2016 there were 6795 Metrocard swipes at the closest station, less than five percent of the daily total. Even if all 330 commuted to Manhattan between 7:30 and 8:30 AM, that would add an average of three people per 167-person subway car.

Schools were overcrowded ten years ago, no doubt. But the city has recently opened two new schools and two new additions to existing schools, and plans to continue building more. The claim that the street was inadequate for the traffic is similarly false. It handles all the cars and trucks for the existing lot, and the proposal includes plans to build the missing sidewalk on the south side of the street.

A common theme was that “the entire community” was against this project. I was not opposed. I was slightly in favor, despite the oversupply of parking, because I found all the reasons for opposition incredibly thin, and I figured it would modestly increase the housing supply and thus help to bring down rents. I never heard any enthusiastic support, but there were plenty of people who were not opposed. I occasionally disputed some of the more outrageous stories with my neighbors on Facebook, in a respectful and neighborly way, and they got very upset. Some of them unfriended me.

So basically, the rents were going to be relatively affordable. The building was not going to be particularly large or tall for the area. It wasn’t going to increase overcrowding on the subway to any noticeable degree, and the neighborhood was not united in opposition. All the "local knowledge" was completely false.

I was originally going to write a post about how local people lie, similar to one I wrote back in 2012. I don’t think these neighbors of mine are lying, exactly. It’s more what’s been called “bullshit”: a propaganda soup mixed up without regard for truth. But I realized something else about this particular bullshit: it isn’t local.

There is one specific piece of local information: many tenants of the existing complex are not happy with the way the nonprofit has managed their buildings. Everything else is generic boilerplate about a “large real estate developer” looking to build a “massive apartment building.” These are the same things we read in stories from Morristown to Minneapolis.

My neighbors are almost certainly not in the pay of a large multinational corporation dedicated to opposing new housing construction. But they don’t just live in a local world. They read Jeremiah Moss and maybe Jane Jacobs too. They’ve seen at least half a dozen movies where the villain is a large real estate developer looking to build a massive apartment building. They’ve seen people protest new construction on TV, heard it on the radio and read about it in the New York Times. Many of them have friends in other neighborhoods and other cities who are engaged in similar struggles.

Some of them are afraid of the City's plans for Sunnyside Yards, which do sound like the kind of crazy, destructive thing Robert Moses used to do. Never mind all the differences, never mind that they've quietly acquiesced to the much more wasteful and destructive Kosciuszko Bridge replacement; they see this 200+ unit apartment building as the thin end of the wedge

They need no coaching; they know the script. Out of context, massive traffic jams, casting shadows, destroying the character of the neighborhood. The transit angle is something you don’t get everywhere, but these days you hear it wherever there’s a train. The rest of it is just a re-enactment of the same story they’ve heard dozens of times, with them in the role of the Local Heroes who Band Together. That’s why they unfriended me: I was saying the wrong lines.

These residents appear to display local knowledge (“we have a parking shortage”) but it is fake local knowledge disconnected from local reality, a prop to brandish during their performance. Similarly, “the community” is a prop, a fake community with fake unity, standing in for the real communities that inhabit the neighborhood, barely aware of each other, each with its own corrupt decision-making process and its multitudes of alienated minorities.

This is actually the opposite of the often-repeated fable of the Wise Locals against the Clueless Planner. The planner might not live in the neighborhood (though some of my neighbors are planners), but with some careful observation they could come up with more reliable local knowledge than anything produced by the opponents of this project.

The real lesson to take from the failures of central planning is not the value of local knowledge, but the value of humility. And the lesson we should take from the failure of this project is that local residents can be just as bereft of humility as anyone else, with consequences that are just as dire in the aggregate as the consequences of Robert Moses's hubris.

After a few contentious meetings, stories emerged in the news and on Facebook, and were eventually published in a change.org petition and a website: the rents would be sky-high, the new building would be massive and out of context, and it would dump hundreds of new riders on the already overcrowded elevated train and neighborhood schools. The street was not adequate to handle the traffic. The entire community was against it. Eventually the City Council member declared that he was against the project, and it was dropped.

Last week I heard someone on a podcast talking about the value of local knowledge in city planning, crediting Jane Jacobs for it. Certainly, Jacobs catalogs a number of clear cases where planners came into an area with little or no knowledge of it, and royally messed it up. She might have declared the defeat of this project to be a triumph of local knowledge.

The problem is that all the stories I listed above were false. The existing building is run by a nonprofit specifically dedicated to providing affordable housing, and their plans for the site specified that the vast majority of the rents would be below market. The existing building, built in 1931, is a superblock with 472 units. Less than a block away are two more complexes with over 400 units each. Two blocks away is a row of four twelve-story towers-in-a-parking lot on top of a hill. This building would fit in completely with the existing context.

The impacts on transit are similarly overstated. First of all, some people won’t be commuting to Manhattan anyway. They could be retired, or telecommuting, or working elsewhere. And unfortunately, some won’t be commuting by train. In 2008, Rachel Weinberger wrote a great report called “Guaranteed Parking, Guaranteed Driving,” demonstrating that if you include parking with housing, people are much more likely to drive. The plans called for 220 units in the new building, and about as many parking spaces, which sounds dreadful. Based on Weinberger’s research we can predict that those 220 spaces would induce a lot of driving.

Of course some people will take the train no matter what happens, and that number will probably increase as more people realize that driving is a pain in the ass. So let’s imagine that these 220 apartments produce a really high number of transit commuters to Manhattan, say 330, or an average of 1.5 commuters per apartment, including two-bedrooms, one-bedrooms and studios. According to the MTA, on the average weekday in 2016 there were 6795 Metrocard swipes at the closest station, less than five percent of the daily total. Even if all 330 commuted to Manhattan between 7:30 and 8:30 AM, that would add an average of three people per 167-person subway car.

Schools were overcrowded ten years ago, no doubt. But the city has recently opened two new schools and two new additions to existing schools, and plans to continue building more. The claim that the street was inadequate for the traffic is similarly false. It handles all the cars and trucks for the existing lot, and the proposal includes plans to build the missing sidewalk on the south side of the street.

A common theme was that “the entire community” was against this project. I was not opposed. I was slightly in favor, despite the oversupply of parking, because I found all the reasons for opposition incredibly thin, and I figured it would modestly increase the housing supply and thus help to bring down rents. I never heard any enthusiastic support, but there were plenty of people who were not opposed. I occasionally disputed some of the more outrageous stories with my neighbors on Facebook, in a respectful and neighborly way, and they got very upset. Some of them unfriended me.

So basically, the rents were going to be relatively affordable. The building was not going to be particularly large or tall for the area. It wasn’t going to increase overcrowding on the subway to any noticeable degree, and the neighborhood was not united in opposition. All the "local knowledge" was completely false.

I was originally going to write a post about how local people lie, similar to one I wrote back in 2012. I don’t think these neighbors of mine are lying, exactly. It’s more what’s been called “bullshit”: a propaganda soup mixed up without regard for truth. But I realized something else about this particular bullshit: it isn’t local.

There is one specific piece of local information: many tenants of the existing complex are not happy with the way the nonprofit has managed their buildings. Everything else is generic boilerplate about a “large real estate developer” looking to build a “massive apartment building.” These are the same things we read in stories from Morristown to Minneapolis.

My neighbors are almost certainly not in the pay of a large multinational corporation dedicated to opposing new housing construction. But they don’t just live in a local world. They read Jeremiah Moss and maybe Jane Jacobs too. They’ve seen at least half a dozen movies where the villain is a large real estate developer looking to build a massive apartment building. They’ve seen people protest new construction on TV, heard it on the radio and read about it in the New York Times. Many of them have friends in other neighborhoods and other cities who are engaged in similar struggles.

Some of them are afraid of the City's plans for Sunnyside Yards, which do sound like the kind of crazy, destructive thing Robert Moses used to do. Never mind all the differences, never mind that they've quietly acquiesced to the much more wasteful and destructive Kosciuszko Bridge replacement; they see this 200+ unit apartment building as the thin end of the wedge

They need no coaching; they know the script. Out of context, massive traffic jams, casting shadows, destroying the character of the neighborhood. The transit angle is something you don’t get everywhere, but these days you hear it wherever there’s a train. The rest of it is just a re-enactment of the same story they’ve heard dozens of times, with them in the role of the Local Heroes who Band Together. That’s why they unfriended me: I was saying the wrong lines.

These residents appear to display local knowledge (“we have a parking shortage”) but it is fake local knowledge disconnected from local reality, a prop to brandish during their performance. Similarly, “the community” is a prop, a fake community with fake unity, standing in for the real communities that inhabit the neighborhood, barely aware of each other, each with its own corrupt decision-making process and its multitudes of alienated minorities.

This is actually the opposite of the often-repeated fable of the Wise Locals against the Clueless Planner. The planner might not live in the neighborhood (though some of my neighbors are planners), but with some careful observation they could come up with more reliable local knowledge than anything produced by the opponents of this project.

The real lesson to take from the failures of central planning is not the value of local knowledge, but the value of humility. And the lesson we should take from the failure of this project is that local residents can be just as bereft of humility as anyone else, with consequences that are just as dire in the aggregate as the consequences of Robert Moses's hubris.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

The challenge of curbside transit lanes

Back in May I argued that we should be talking about improving surface transit even for avenues with subways or els, for three reasons. First, it can help calm speeding personal cars and trucks. Second, it can provide local hop-on, hop-off service, which is especially valuable to people who have difficulty walking or climbing stairs. Third, especially with New York’s high construction costs and deference to NIMBYs, it can accommodate increases in demand in much less time than building a subway or el.

A couple of weeks ago Sandy Johnston tweeted a great picture from Lisbon to illustrate that street-level transit does not need huge boulevards; the minimum width is not much more than the width of the vehicle. Of course, for it to be rapid transit the route has to be unimpeded by private vehicles, but we could never get a useful network if we only built transitways on our widest boulevards.

The city does have an extensive network of hundred foot avenues, and we can have a decent surface-level rapid transit network once we find reliable ways of making transit rapid within a hundred feet. So what arrangement of road space would do the most to discourage single-occupant driving while still allowing people to get to work and shopping, and to receive and ship things? I’ll talk in future posts about what has worked in the past and what might work in the future, but today I need to talk about a couple of things that don’t work.

The Department of Transportation originally proposed banning vehicles other than transit on Thirty-Fourth Street. That can work; I’ve seen it work on Fulton Street in Brooklyn and yes, on State Street in Chicago. But it only works if businesses can still receive deliveries. I’m not sure what they do in Brooklyn, but I know in Chicago they have alleys. I’ve read promising things about deliveries by trolley and bicycle, but until those are closer let’s plan for some private vehicles, especially on wider avenues.

The Department of Transportation has tried reserving the entire curbside lane for buses on avenues like Second Avenue and 34th Street, with unsatisfying results. To begin with there’s always a major outcry from residents and business owners, who are used to having the curbside lane for turning, unloading and customer parking - and more often than not, parking for residents and business owners.

The city has compromised on this issue in a very counterproductive way, by suspending the bus lanes to allow private loading and even parking during middays, nights and weekends, and allowing turning and passenger dropoffs at all times. But they still painted the lane red, teaching drivers that the lanes don’t really matter and making things harder for an already uninterested NYPD.

I’m not entirely sympathetic: it’s been shown that for businesses in walkable neighborhoods in New York, the majority of customers arrive on foot, by bus or by train. The guy who gets his Goya beans delivered to his apartment on 34th Street can have them wheeled around the corner on a handtruck. But as I wrote a few years ago, a lane for parking suits our goals better than a lane for moving cars. If we have a hundred feet to work with, minus sidewalk and transit lanes, I’d rather fill the rest of the space with a traffic lane and a parking/loading lane than two traffic lanes.

Curbside bus lanes can work fairly well in places like the west side of Fifth Avenue where there are no businesses and relatively few turns - although even that lane would benefit from better enforcement. On avenues with businesses and intersections, it’s not the best approach. I’ll talk about other possibilities in future posts.

A couple of weeks ago Sandy Johnston tweeted a great picture from Lisbon to illustrate that street-level transit does not need huge boulevards; the minimum width is not much more than the width of the vehicle. Of course, for it to be rapid transit the route has to be unimpeded by private vehicles, but we could never get a useful network if we only built transitways on our widest boulevards.

The city does have an extensive network of hundred foot avenues, and we can have a decent surface-level rapid transit network once we find reliable ways of making transit rapid within a hundred feet. So what arrangement of road space would do the most to discourage single-occupant driving while still allowing people to get to work and shopping, and to receive and ship things? I’ll talk in future posts about what has worked in the past and what might work in the future, but today I need to talk about a couple of things that don’t work.

The Department of Transportation originally proposed banning vehicles other than transit on Thirty-Fourth Street. That can work; I’ve seen it work on Fulton Street in Brooklyn and yes, on State Street in Chicago. But it only works if businesses can still receive deliveries. I’m not sure what they do in Brooklyn, but I know in Chicago they have alleys. I’ve read promising things about deliveries by trolley and bicycle, but until those are closer let’s plan for some private vehicles, especially on wider avenues.

The Department of Transportation has tried reserving the entire curbside lane for buses on avenues like Second Avenue and 34th Street, with unsatisfying results. To begin with there’s always a major outcry from residents and business owners, who are used to having the curbside lane for turning, unloading and customer parking - and more often than not, parking for residents and business owners.

Good thing that bus lane is there to ensure the speedy travel of new yorkers pic.twitter.com/w7nvTyLGbj

— eric goldwyn (@ericgoldwyn) August 21, 2017

The city has compromised on this issue in a very counterproductive way, by suspending the bus lanes to allow private loading and even parking during middays, nights and weekends, and allowing turning and passenger dropoffs at all times. But they still painted the lane red, teaching drivers that the lanes don’t really matter and making things harder for an already uninterested NYPD.

I’m not entirely sympathetic: it’s been shown that for businesses in walkable neighborhoods in New York, the majority of customers arrive on foot, by bus or by train. The guy who gets his Goya beans delivered to his apartment on 34th Street can have them wheeled around the corner on a handtruck. But as I wrote a few years ago, a lane for parking suits our goals better than a lane for moving cars. If we have a hundred feet to work with, minus sidewalk and transit lanes, I’d rather fill the rest of the space with a traffic lane and a parking/loading lane than two traffic lanes.

Curbside bus lanes can work fairly well in places like the west side of Fifth Avenue where there are no businesses and relatively few turns - although even that lane would benefit from better enforcement. On avenues with businesses and intersections, it’s not the best approach. I’ll talk about other possibilities in future posts.

Saturday, July 15, 2017

Buy American Sprawl

The American Action Forum recently released a critique of “Buy America” laws on the basis that they place undue hardship on transit agencies and set a ceiling on the quality of the equipment they use. I’m not one to put a lot of trust in Republican think-tanks, but I’ve heard similar critiques from transit advocates across the political spectrum.

The idea of "buy America" is initially appealing, especially when you hear about the horrendous conditions in sweatshops overseas. But there are lots of European and East Asian companies that have better working conditions than you find in factories in the United States. In fact, the “American” trains are frequently assembled in the US in a factory owned by one of these companies, out of parts produced by factories in other countries owned by the same company.

The main argument for "buy America" in transit that holds up to any scrutiny is the idea of maintaining or boosting our manufacturing capability. Because of "buy America," there are American citizens in Plattsburgh, Yonkers and Portland who know how to make trains. If the market grows again some day, there may be enough business for an American company to hire some of these workers and go into competition with Bombardier, Kawasaki and Alstom.

Another argument is that manufacturing transit locally builds the constituency for transit. People who might never ride the subway fight for subway funding, because they build the subways. This is potentially valuable for New York, where our tax money is regularly diverted to road building under the guise of "parity for upstate."

Unfortunately, that potential rarely seems to work out. It’s impossible to tell which legislators supported what project and which ones opposed it, because they do everything in secret. But the bottom line is that these plants have been running for decades and our transit systems are underfunded every year by the Legislature.

Whenever I take the Hudson River Line I like going past the Kawasaki factory in Yonkers. Here’s a former Otis elevator factory making trains for the New York Subway that’s only a few miles from the subway itself. More importantly, it’s walking distance from home for many low-income workers, and a short transit ride for millions.

Contrast the walkable downtown Kawasaki factory with the Bombardier factory built in the 1990s on a decommissioned Air Force base in Plattsburgh. This is an unpleasant forty-minute walk from downtown, and relatively few people live nearby.

There is a bus that runs hourly and stops outside the plant, but it runs in a circle, so the trip back takes forty minutes. I’m guessing the vast majority of workers drive.

The Alstom plant in Hornell, where the new Acela train cars will be assembled, is a bit better. It was built by the Erie Railroad in the nineteenth century, so it was built to be walkable.

But Hornell has no passenger train service, and it is served by only one bus a day to Rochester, and another going back to Elmira. At least Plattsburgh has nine buses a day to Albany, plus daily Amtrak service.

The new CRRC plant in Springfield where they'll be building the new MBTA cars looks like it'll be super sprawly and unwalkable from the renderings.

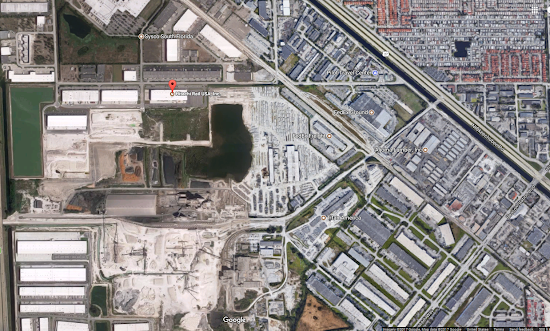

But if you check out the location on Google Maps it actually looks much better: twenty minutes from downtown on the G2 bus. On the other hand, Siemens's plant in Sacramento is sprawly and a twenty minute walk from the nearest bus stop:

Kawasaki may have built a very walkable and transit-oriented plant in Yonkers, but their plant in Lincoln, where the new WMATA subway cars are being built, is out in the cornfields near the airport, a 35-minute walk from the nearest bus:

Even the Hitachi plant in Medley, Florida, where the trains for the Miami Metrorail are made, is almost two hours from downtown Miami, including an hour by bus from the nearest Metrorail station in Hialeah and then a half hour walk:

So you might have noticed that we're fighting for money to be spent on transit, and it goes to pay people who never take transit, and in many cases couldn't take transit if they wanted to. And what if we didn't have Buy America? Well, notice that all these companies are headquartered in other countries? Some of the manufacturing (and in some cases, most of the manufacturing) is done at plants owned by the same company and located in other countries.

In the case of Bombardier, many of New York's subway cars are made at this old snowmobile plant 87 miles north of Québec city, with no bus or train service.

On the other hand, the main Alstom plant in Valenciennes, France is a half-hour by tram from the main Valenciennes train station - which has multiple trains per hour to Paris, including the TGV.

And the Siemens plant in Krefeld in densely populated Westphalia, is a half hour by commuter rail and bus from the main Krefeld train station, with frequent service to Aachen, Duisberg, Cologne and even Mönchengladbach, wherever that is.

The CRRC factory in Changchun is forty minutes from the main train station.

More importantly it's surrounded by hundreds of high-rise apartment buildings, any one of them big enough to comfortably house a sizable chunk of the workforce of these American factories.

And finally, take a look at Kawasaki's main plant in Kobe, less than twenty minutes on foot from the main high-speed rail station, right near the harbor.

Just a few blocks away we see classic Japanese urbanism: residential high-rises and Really Narrow Streets.

The Hitachi Kasado plant in Kudamatsu is slightly sprawlier, but still a short transit or walking commute for thousands of workers.

The bottom line is that when our transit dollars go to China or Japan or Germany or France, they go to people who commute on foot and by train. When they go to Yonkers or Springfield, they may go to some bus or foot commuters. But when they go to Hornell or Plattsburgh or La Pocatière, or even Sacramento or Hialeah, they go to people who never use transit.

Ordinarily this would not be such a big deal; we're talking a few thousand people total, out of millions of car drivers in North America. But if we're counting the number of vehicle-miles traveled eliminated by the purchase of these trains, we need to subtract the vehicle-miles traveled by all those workers.

The other factor is that these contracts are sometimes presented as a way to build electoral support for transit outside of cities. This may be purely a transaction on the electoral level: a legislator votes to fund the transit agency capital plan, and the agency provides jobs in the legislator's district that they can take credit for. But what happens then? How many train cars does New York need? How long will these legislators keep up their end of the bargain? And what happens when the desire of their sprawl-living, long-distance-driving constituents for more and bigger roads conflicts with the needs of transit users (as opposed to transit agency managers)?

I've already made the case that cutting road and parking budgets can often do more to achieve our goals (see the top of the page) than spending more money on transit. Combine that with the fact (documented by the AAF in the report I mentioned at the beginning) that with Buy America our rail car budgets buy only 75% of what they would otherwise, and they encourage people to drive, what are we really getting for our tax dollars?

The idea of "buy America" is initially appealing, especially when you hear about the horrendous conditions in sweatshops overseas. But there are lots of European and East Asian companies that have better working conditions than you find in factories in the United States. In fact, the “American” trains are frequently assembled in the US in a factory owned by one of these companies, out of parts produced by factories in other countries owned by the same company.

The main argument for "buy America" in transit that holds up to any scrutiny is the idea of maintaining or boosting our manufacturing capability. Because of "buy America," there are American citizens in Plattsburgh, Yonkers and Portland who know how to make trains. If the market grows again some day, there may be enough business for an American company to hire some of these workers and go into competition with Bombardier, Kawasaki and Alstom.

Another argument is that manufacturing transit locally builds the constituency for transit. People who might never ride the subway fight for subway funding, because they build the subways. This is potentially valuable for New York, where our tax money is regularly diverted to road building under the guise of "parity for upstate."

Unfortunately, that potential rarely seems to work out. It’s impossible to tell which legislators supported what project and which ones opposed it, because they do everything in secret. But the bottom line is that these plants have been running for decades and our transit systems are underfunded every year by the Legislature.

Whenever I take the Hudson River Line I like going past the Kawasaki factory in Yonkers. Here’s a former Otis elevator factory making trains for the New York Subway that’s only a few miles from the subway itself. More importantly, it’s walking distance from home for many low-income workers, and a short transit ride for millions.

Contrast the walkable downtown Kawasaki factory with the Bombardier factory built in the 1990s on a decommissioned Air Force base in Plattsburgh. This is an unpleasant forty-minute walk from downtown, and relatively few people live nearby.

There is a bus that runs hourly and stops outside the plant, but it runs in a circle, so the trip back takes forty minutes. I’m guessing the vast majority of workers drive.

The Alstom plant in Hornell, where the new Acela train cars will be assembled, is a bit better. It was built by the Erie Railroad in the nineteenth century, so it was built to be walkable.

But Hornell has no passenger train service, and it is served by only one bus a day to Rochester, and another going back to Elmira. At least Plattsburgh has nine buses a day to Albany, plus daily Amtrak service.

The new CRRC plant in Springfield where they'll be building the new MBTA cars looks like it'll be super sprawly and unwalkable from the renderings.

But if you check out the location on Google Maps it actually looks much better: twenty minutes from downtown on the G2 bus. On the other hand, Siemens's plant in Sacramento is sprawly and a twenty minute walk from the nearest bus stop:

Kawasaki may have built a very walkable and transit-oriented plant in Yonkers, but their plant in Lincoln, where the new WMATA subway cars are being built, is out in the cornfields near the airport, a 35-minute walk from the nearest bus:

Even the Hitachi plant in Medley, Florida, where the trains for the Miami Metrorail are made, is almost two hours from downtown Miami, including an hour by bus from the nearest Metrorail station in Hialeah and then a half hour walk:

So you might have noticed that we're fighting for money to be spent on transit, and it goes to pay people who never take transit, and in many cases couldn't take transit if they wanted to. And what if we didn't have Buy America? Well, notice that all these companies are headquartered in other countries? Some of the manufacturing (and in some cases, most of the manufacturing) is done at plants owned by the same company and located in other countries.

In the case of Bombardier, many of New York's subway cars are made at this old snowmobile plant 87 miles north of Québec city, with no bus or train service.

On the other hand, the main Alstom plant in Valenciennes, France is a half-hour by tram from the main Valenciennes train station - which has multiple trains per hour to Paris, including the TGV.

And the Siemens plant in Krefeld in densely populated Westphalia, is a half hour by commuter rail and bus from the main Krefeld train station, with frequent service to Aachen, Duisberg, Cologne and even Mönchengladbach, wherever that is.

The CRRC factory in Changchun is forty minutes from the main train station.

More importantly it's surrounded by hundreds of high-rise apartment buildings, any one of them big enough to comfortably house a sizable chunk of the workforce of these American factories.

And finally, take a look at Kawasaki's main plant in Kobe, less than twenty minutes on foot from the main high-speed rail station, right near the harbor.

Just a few blocks away we see classic Japanese urbanism: residential high-rises and Really Narrow Streets.

The Hitachi Kasado plant in Kudamatsu is slightly sprawlier, but still a short transit or walking commute for thousands of workers.

The bottom line is that when our transit dollars go to China or Japan or Germany or France, they go to people who commute on foot and by train. When they go to Yonkers or Springfield, they may go to some bus or foot commuters. But when they go to Hornell or Plattsburgh or La Pocatière, or even Sacramento or Hialeah, they go to people who never use transit.

Ordinarily this would not be such a big deal; we're talking a few thousand people total, out of millions of car drivers in North America. But if we're counting the number of vehicle-miles traveled eliminated by the purchase of these trains, we need to subtract the vehicle-miles traveled by all those workers.

The other factor is that these contracts are sometimes presented as a way to build electoral support for transit outside of cities. This may be purely a transaction on the electoral level: a legislator votes to fund the transit agency capital plan, and the agency provides jobs in the legislator's district that they can take credit for. But what happens then? How many train cars does New York need? How long will these legislators keep up their end of the bargain? And what happens when the desire of their sprawl-living, long-distance-driving constituents for more and bigger roads conflicts with the needs of transit users (as opposed to transit agency managers)?

I've already made the case that cutting road and parking budgets can often do more to achieve our goals (see the top of the page) than spending more money on transit. Combine that with the fact (documented by the AAF in the report I mentioned at the beginning) that with Buy America our rail car budgets buy only 75% of what they would otherwise, and they encourage people to drive, what are we really getting for our tax dollars?

Monday, June 19, 2017

How we get safer crosstown streets

The killing of Citibike rider Dan Hanegby by a Short Line bus driver on West Twenty-Sixth Street this week highlighted a number of critical problems with the way buses are managed in Manhattan, and pointed up serious conflicts and contradictions in the agendas of transit, pedestrian and cycling advocates in the New York area and beyond.

It’s true that buses are dangerous to cyclists, and to pedestrians as well. The person who has always articulated this most clearly and forcefully has been Peter Smith. In a guest piece for Cyclelicious he focuses on “Bus Rapid Transit”; in a comment on a Greater Greater Washington post he talks about buses and bikes in general, and in a comment on a Bike Portland post he specifically discusses cases where bus drivers hit cyclists.

On a basic level, Smith is right: if we are really committed to Vision Zero, "the end goal is to do away with all vehicles that cannot live harmoniously with human beings — buses and cars should be the first to go." And although he claims that buses are more scary than cars, he also says that "the single occupancy vehicle in the city is the greatest manifestation of that evil—so it shouldn’t be tolerated."

If buses (and cars and trucks) cannot coexist with cyclists and pedestrians, what do we do about it? Smith’s vision is primarily centered around bikes and pedestrians, but sometimes people want to go further than they can bike. Sometimes we want to carry things - maybe very big things. And sometimes we can’t walk or bike at all. The answer, of course, is trains, as I’ve written before, and as @DoorZone wrote on Twitter in response to this tragedy:

NYC should only allow vehicles w/ governors, dead man's switches, & w/out horns south of 60th St. https://t.co/dalSbAOqH8

— DoorZone (@D00RZ0NE) June 16, 2017

That’s a lovely vision of the future, but how do we get to it? Even the wise cannot see all ends, but it seems like gradually investing more and more in rail (including at-grade trolleys), pedestrian and cycling infrastructure, and ending subsidies and requirements for roads and parking will lead to an incremental shift away from cars, buses and trucks and towards trains, bikes and walking. I think we can also do more with wheelbarrows, hand carts, cargo bikes and other non-motorized freight carriers than we currently do.

Unfortunately, our city’s advocates for walking and cycling aren’t conducting anything like a coherent campaign to shift our long-distance and heavy-goods movement from cars, buses and trucks to trains and trolleys. In fact, many of them are actively hostile to subways and trolleys, treating them as luxuries for the rich. In contrast, they elevate walking, cycling - and buses. In particular, they are fond of "Bus Rapid Transit," which they see as cheap, quick and democratic, and sometimes explicitly tout as a "surface subway."

These proposals are often presented as ways to get working-class New Yorkers to from homes outside of Manhattan to jobs outside of Manhattan, but there are still lots of jobs in Manhattan, and it’s a convenient transfer point to get to other parts of the metro area. In particular, there are lots of working-class people who live in parts of New Jersey and Rockland County where the bus is the most convenient way to get to work - and in fact, the Lincoln Tunnel Exclusive Bus Lane is the most rapid bus facility in the metro area.

But because of the way buses are mismanaged in New York City, there are almost no through-running bus lines. People from New Jersey have to get off the bus at or near the Port Authority Bus Terminal and make their way to jobs or shopping, usually by transferring to a subway.

The "Bus Rapid Transit" boosters are right about one aspect of buses: they can be scaled up quickly in response to increased demand. This worked very well when demand for transit rose beginning in 2007, in response to rising gas prices and crashing home equity. People began taking the bus in greater numbers, not just to get from the New Jersey suburbs in to Manhattan, but from cities like Philadelphia and Washington, and even further afield through the Chinatown bus network and relative newcomers like Megabus, Bolt and Vamoose.

The problem was that the "BRT" facility - the Exclusive Bus Lane and the Port Authority Bus Terminal that it feeds into - were already over capacity. So our "BRT" activists immediately demanded that it be expanded, right? No, they were actually pretty quiet about it, which left the bus operators to establish pick-up spots on the street, at handy transfer points in Manhattan, particularly Chinatown and Midtown.

When NIMBY "community members" came out to complain about the buses, were our “BRT” activists there to oppose them? No, they were pretty much AWOL, as they had been when NIMBYs torpedoed the 34th Street Busway. They did nothing as the State Senate forced bus operators to run a gauntlet of NIMBYs before they could legally pick up passengers on the street, and they haven’t had the power to increase off-street infrastructure.

Despite Peter Smith’s allegations I have not seen any proof that buses are any more dangerous than cars. In fact, we would expect them to be less dangerous, since they are operated by trained professionals with their careers potentially on the line. And yet self-proclaimed pedestrian advocates like Christine Berthet continue to repeat these allegations and to lobby for ever-greater restrictions on buses, and others in the livable streets movement echo them.

So what should we do to make our streets safer for cyclists? Some have called for physically separated crosstown bike lanes at key intervals. I like this idea. But what if you’re riding to a destination - or to a Citibike station - that isn’t on one of those streets? Can we create physically separated lanes on every street in the city? I don’t think that’s feasible or necessary.

As I’ve been arguing for years, we need to reconfigure our "side" streets as yield streets. They are all at least sixty feet wide. If you’ve ever been on one when it’s closed for construction or events, you know that they have plenty of room for two-way car traffic, and a hundred years ago they were all two-way. They can even accommodate a lane of parked cars on each side, plus a lane of moving cars in each direction, as long as the vehicles are all relatively narrow. When people started double parking it caused congestion, so the city changed them to one-way traffic flow - which has in turn led to a large increase in traffic as drivers circle the blocks. But when there is no double-parking the driving lane is extra wide, which leads to drivers speeding and crowding out cyclists.

The solution, as recommended by Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and the NACTO Street Design Guide, is to reserve space for loading zones throughout the length of each block, return all the streets to two-way flow, and ramp up enforcement of double parking. Then it is important to monitor the situation and increase the space for loading zones as necessary. Additional traffic calming measures like chicanes and pavement treatments may be necessary. If the design is implemented properly, drivers will be deterred from speeding by the prospect of a head-on collision, and will be less likely to pressure cyclists into the door zones.

You might have wondered why, instead of 26th Street in Manhattan where Dan Hornegby was killed, I used a picture of the 137-00 block of 45th Avenue in Flushing to illustrate an over-wide one-way cross street. As you can see from the second photo, the rest of the blocks on 45th Avenue are two-way, and people drive much more slowly and carefully. (Holly Avenue, one block south, is the same width, two-way, and a bus route.) Again, these yield streets are not a substitute for protected bike lanes, but a treatment for streets that are not chosen as high-priority cycling corridors. In other words, it should be the default configuration for all streets that are less than eighty feet wide.

In the long term, yes, we do need to get buses off our streets, but the urgency to get private cars off the streets is just as great. In the short term, we could do a lot more to accommodate buses in Manhattan, like facilitating through-running and stops on major crosstown streets. To make crosstown streets safer for cyclists, we should implement protected bike lanes leading to Citibike stations near all Midtown subway stations. The rest of the crosstown streets should be reconfigured as two-way yield streets.

Sunday, June 11, 2017

Long distance coaches should carry bikes

A couple of years ago I was in Penn Station and heard an announcement about bustitution due to track work. The announcer informed us that the buses would not be able to accept bikes. Just the day before I had been talking with some people about cycling in Montreal. I haven't had a chance to experience it, because I haven't been there since before they rolled out the Bixi bike share. Years ago I had planned to bring my bike there on a visit, but there was bustitution and Amtrak informed me I wouldn't be allowed to take the bike on the substitute buses.

In many small cities, government-run local buses are equipped with a front rack that can hold two or three bicycles. But the policy of long distance, usually private, coach operators (at least in North America) is typically that they will only allow bikes to be stored in the cargo bins if they are in boxes, with the handlebars removed. Of course, it is very difficult for a bicycle rider to carry a box large enough to hold the bike, and removing and reattaching handlebars requires time, skill and specialized tools.

Why do they do this? It smells to me of that toxic combination of elitism and liability worries that makes it painful to interact with American corporations. The owners and executives of the coach companies don't take their own buses, and they don't ride bikes. They don't want to take bikes on the coaches: they take up a lot of space, it's time-consuming for the drivers, and they're afraid of being sued if the bikes get broken. Their lawyers said something about liability, so they made a rule: no bikes.

If we could get long distance coaches to accept bicycles in a convenient way, this could easily be used to extend the coach network, with a measurable benefit to the lives of people who don't own cars. When I was a teenager, I was essentially cut off from all the jobs at the local mall because it was five miles from the nearest coach station. The roads from the bus station to the mall were relatively friendly to bike riders, but the roads from my town to the bus station were not. This would also encourage people to take a coach for tourism.

I’ve seen a few blog posts by bike advocates in favor of racks on city buses, or space for bikes on trains. But I don’t recall ever seeing one in favor of convenient bike storage on long-distance coaches. Do you know any coach operators that carry bikes conveniently? Was there anything that overcame their objections and persuaded them to do this?

Tuesday, May 23, 2017

Better transit on the hundred foot avenues

We’ve got them all over New York City: avenues that are a hundred feet wide from property line to property line. Some of them are dangerous speedways like Gun Hill Road in the Bronx, and some are congested urban business corridors like Atlantic Avenue in Boerum Hill. Some run through transit deserts like Little Neck Parkway, while others have four-track subways and multiple bus lines like Seventh Avenue in Manhattan.

I wish I could point to a single one of these and say that its configuration is ideal for our goals, but even Seventh Avenue has many shortcomings That said, some of these avenues are clearly better than others for local transit, some are better than others for long-distance transit, and some are better than others for pedestrian comfort and convenience.

I’ve realized that these avenues work as interesting case studies for how terrain, politics, land use and function interact to produce environments that are better or worse for transit and walking. Transit and pedestrian improvements can be independent, or they can complement each other. Running transit underground, as on Fourth Avenue in Brooklyn, or elevating it, as on Brighton Beach Avenue, is great for transit speed, frequency and reliability, but it’s no guarantee of a safe and comfortable pedestrian environment. Rezoning to allow and encourage shops and residences right next to the sidewalk can also improve conditions for pedestrians.

I’ve talked a lot about subways and els already. You know I’m in favor of them. But while we’re fighting for grade-separated rapid transit - or even if we have it - we still need to talk about surface transit. Surface transit is great for short, local trips, especially for people with mobility impairments, and reallocating street space from mixed traffic to transit, pedestrians or even parking can improve conditions for walking.

I’m planning a series of posts that explore some of these hundred foot avenues and evaluate particular strategies for their effectiveness in promoting transit or walking, or both. Stay tuned!

Friday, January 27, 2017

Do we need the Port Authority Bus Terminal?

In 2015 I talked about the proposal to build a new bus terminal in downtown Flushing, and came up with the following list of six features. The current Port Authority terminal on 41st Street provides some of these some of the time:

Any transit system is easier and more attractive with one-stop shopping, short-term bus layovers and easy transfers. But long-term bus layovers, avoiding congestion and passenger facilities are more important for long distance trips than short ones.

If I’m taking the bus to Binghamton, I might have to wait an hour or more, so it’s really important for me to have shelter, bathrooms, tickets and food. (It would be nice to have seating and a place to store my bag, but that’s a whole other post.)

Cheaper services with higher frequency, like the New Jersey Transit 166 bus, don’t need a terminal, any more than the M5 does. Of course we all need safe places to pee and grab a snack, but people waiting fifteen minutes for a half hour New Jersey Transit bus ride don’t have any more need than people waiting fifteen minutes for a half hour New York City Transit bus ride.

All movement is quicker if you don’t have a lot of people or vehicles in your way. But for someone who’s getting off right on the other end of the Lincoln Tunnel, going up three flights of stairs cuts out most of that time savings. Trips with more than a mile between stops benefit more from grade separation, because they have the time for a bus to get up to speed.

As I pointed out in my post on the proposed Flushing bus terminal, there are actually advantages to having buses pick up and drop off on the street. It allows for through-running, so that passengers whose destination is beyond the terminus can just stay on the bus, which then heads out to a layover point in a less congested area. Street pickups can also make transfers more efficient and robust by spreading them out across multiple stops.

Street-level transfers are better for the local economy. Bathrooms and shelter are public goods that need to be provided by the government, but food and shopping? That’s what downtown streets are for, in a very real sense. In Flushing the streets do an excellent job of providing snacks, drinks and banking for bus and train passengers. A government-owned building filled with corporate concessions is necessarily less dynamic and less friendly to small businesses.

The Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown provides all these services for long-distance bus lines like Greyhound, Peter Pan and Adirondack Trailways, but it claims to have no room for other long-distance carriers like Megabus, Fung Wah, Vamoose and Hampton Jitney. Some of these companies claim they save passengers money by not paying gate fees to the Port Authority, which is another way of saying that the City doesn’t charge enough for what is essentially a rental of valuable commercial real estate.

Other bus companies say that they offer more convenient pickups in Chinatown and the Upper East Side. But that just begs the question: if bus terminals are so great, why we don’t have them for every direction that buses go? Someone decided it was better to have apartment buildings at the mouth of the Midtown Tunnel, and office buildings near the Holland Tunnel. Were they wrong?

The other claim, that there is no room in the Port Authority terminal for Bolt and LimoLiner, is also questionable. Why do Red and Tan, Academy and Suburban load all their buses in the terminal, when most of them leave frequently for short runs? Why is New Jersey Transit, a government-owned provider of short-haul services, the biggest carrier in the terminal?

Imagine if New Jersey Transit shifted just half of their bus pickups to the street. First of all, I’ve been told that there are more jobs in East Midtown than near the Port Authority. Some of the buses could pick people up and drop them off closer to their jobs. Second, the buses could provide transfers to other trains beside the Seventh and Eighth Avenue, Broadway and 41st Street lines. That would all take a load off the E, 7 and Shuttle trains.

Moving some local NJ Transit buses to the street would free up space in the terminal. I’ve heard that the tight schedules are a source of delays, so just having more wiggle room would improve reliability on the remaining routes. This would still leave room to bring in some long distance services off the street. If it turns out we still need room for long distance services, we can move more NJ Transit buses to the street, as well as some of the shorter, more frequent runs by private carriers.

Some people might complain that the buses would just get stuck in Midtown traffic. This is why it is essential to give them, and the jitney vans, full access to the dedicated bus lanes on 34th, 42nd and 57th Streets, and to make those lanes real busways instead of the half-assed arrangement we’ve had since the DOT botched the process on 34th Street. It would also help to make them true through-running routes, going through the Midtown Tunnel or over the Queensboro Bridge.

You may have heard that the Port Authority board has declared its bus terminal to be at the end of its life, and said that it wants to use eminent domain to acquire a new property somewhere west of the current terminal, build a new terminal there at a cost of billions of dollars, and sell the current terminal to developers. The main thing wrong with this is that it would be horrible for subway transfers.

It’s bad enough to have a terminal where only the east end touches Eighth Avenue, meaning that some passengers have to walk more than two avenue blocks to get to their trains. The Port Authority Board wants to add at least another full avenue block. From what I’ve heard, most of these people have chauffeurs and all of them have free parking, and they’re baby boomers who equate driving with success, so none of them ever make this transfer.

Stephen Smith has argued that any amount in the billions should be spent building enough train tunnels under the Hudson to accommodate all the bus passengers, so that bus transfers can be made in New Jersey, and the terminal can be torn down and not replaced.

I agree with Stephen’s vision as the ultimate goal, but in the medium term there will be short trips that are best made by bus through the Lincoln Tunnel, and those trips should have access to our streets for pickup and dropoff. There will also be long distance bus trips that will be more convenient if they connect to the subway than to a commuter train, and we should have a terminal for them in Manhattan.

The good news is that a terminal serving a few long-distance routes can be much smaller than the current one. It could fit on the site of the South Wing of the current terminal, and probably doesn’t need as many levels - or the parking garage. If that wing really needs to be rebuilt, some of the buses could be relocated temporarily to the lower level of the North Wing - or the Farley Post Office.

The bottom line is that we don’t need a huge bus terminal if we have trains. If we want to spend billions improving our transit system, rail is a much more efficient, sustainable and wise place to spend it.

- One-stop shopping for buses.

- Easy transfer between buses, and from buses to trains.

- Short-term bus layovers.

- Long-term bus layovers.

- Avoiding street congestion. There are ramps for the upper level, and an outbound tunnel under Ninth Avenue. This leaves many buses stuck in traffic, particularly those heading north and east.

- Ticketing, shelter, bathrooms, food and shopping for people waiting for buses.

Any transit system is easier and more attractive with one-stop shopping, short-term bus layovers and easy transfers. But long-term bus layovers, avoiding congestion and passenger facilities are more important for long distance trips than short ones.

If I’m taking the bus to Binghamton, I might have to wait an hour or more, so it’s really important for me to have shelter, bathrooms, tickets and food. (It would be nice to have seating and a place to store my bag, but that’s a whole other post.)

Cheaper services with higher frequency, like the New Jersey Transit 166 bus, don’t need a terminal, any more than the M5 does. Of course we all need safe places to pee and grab a snack, but people waiting fifteen minutes for a half hour New Jersey Transit bus ride don’t have any more need than people waiting fifteen minutes for a half hour New York City Transit bus ride.

All movement is quicker if you don’t have a lot of people or vehicles in your way. But for someone who’s getting off right on the other end of the Lincoln Tunnel, going up three flights of stairs cuts out most of that time savings. Trips with more than a mile between stops benefit more from grade separation, because they have the time for a bus to get up to speed.

As I pointed out in my post on the proposed Flushing bus terminal, there are actually advantages to having buses pick up and drop off on the street. It allows for through-running, so that passengers whose destination is beyond the terminus can just stay on the bus, which then heads out to a layover point in a less congested area. Street pickups can also make transfers more efficient and robust by spreading them out across multiple stops.

Street-level transfers are better for the local economy. Bathrooms and shelter are public goods that need to be provided by the government, but food and shopping? That’s what downtown streets are for, in a very real sense. In Flushing the streets do an excellent job of providing snacks, drinks and banking for bus and train passengers. A government-owned building filled with corporate concessions is necessarily less dynamic and less friendly to small businesses.

The Port Authority Bus Terminal in Midtown provides all these services for long-distance bus lines like Greyhound, Peter Pan and Adirondack Trailways, but it claims to have no room for other long-distance carriers like Megabus, Fung Wah, Vamoose and Hampton Jitney. Some of these companies claim they save passengers money by not paying gate fees to the Port Authority, which is another way of saying that the City doesn’t charge enough for what is essentially a rental of valuable commercial real estate.

Other bus companies say that they offer more convenient pickups in Chinatown and the Upper East Side. But that just begs the question: if bus terminals are so great, why we don’t have them for every direction that buses go? Someone decided it was better to have apartment buildings at the mouth of the Midtown Tunnel, and office buildings near the Holland Tunnel. Were they wrong?

The other claim, that there is no room in the Port Authority terminal for Bolt and LimoLiner, is also questionable. Why do Red and Tan, Academy and Suburban load all their buses in the terminal, when most of them leave frequently for short runs? Why is New Jersey Transit, a government-owned provider of short-haul services, the biggest carrier in the terminal?

Imagine if New Jersey Transit shifted just half of their bus pickups to the street. First of all, I’ve been told that there are more jobs in East Midtown than near the Port Authority. Some of the buses could pick people up and drop them off closer to their jobs. Second, the buses could provide transfers to other trains beside the Seventh and Eighth Avenue, Broadway and 41st Street lines. That would all take a load off the E, 7 and Shuttle trains.

Moving some local NJ Transit buses to the street would free up space in the terminal. I’ve heard that the tight schedules are a source of delays, so just having more wiggle room would improve reliability on the remaining routes. This would still leave room to bring in some long distance services off the street. If it turns out we still need room for long distance services, we can move more NJ Transit buses to the street, as well as some of the shorter, more frequent runs by private carriers.

Some people might complain that the buses would just get stuck in Midtown traffic. This is why it is essential to give them, and the jitney vans, full access to the dedicated bus lanes on 34th, 42nd and 57th Streets, and to make those lanes real busways instead of the half-assed arrangement we’ve had since the DOT botched the process on 34th Street. It would also help to make them true through-running routes, going through the Midtown Tunnel or over the Queensboro Bridge.

You may have heard that the Port Authority board has declared its bus terminal to be at the end of its life, and said that it wants to use eminent domain to acquire a new property somewhere west of the current terminal, build a new terminal there at a cost of billions of dollars, and sell the current terminal to developers. The main thing wrong with this is that it would be horrible for subway transfers.

It’s bad enough to have a terminal where only the east end touches Eighth Avenue, meaning that some passengers have to walk more than two avenue blocks to get to their trains. The Port Authority Board wants to add at least another full avenue block. From what I’ve heard, most of these people have chauffeurs and all of them have free parking, and they’re baby boomers who equate driving with success, so none of them ever make this transfer.

Stephen Smith has argued that any amount in the billions should be spent building enough train tunnels under the Hudson to accommodate all the bus passengers, so that bus transfers can be made in New Jersey, and the terminal can be torn down and not replaced.

I agree with Stephen’s vision as the ultimate goal, but in the medium term there will be short trips that are best made by bus through the Lincoln Tunnel, and those trips should have access to our streets for pickup and dropoff. There will also be long distance bus trips that will be more convenient if they connect to the subway than to a commuter train, and we should have a terminal for them in Manhattan.

The good news is that a terminal serving a few long-distance routes can be much smaller than the current one. It could fit on the site of the South Wing of the current terminal, and probably doesn’t need as many levels - or the parking garage. If that wing really needs to be rebuilt, some of the buses could be relocated temporarily to the lower level of the North Wing - or the Farley Post Office.

The bottom line is that we don’t need a huge bus terminal if we have trains. If we want to spend billions improving our transit system, rail is a much more efficient, sustainable and wise place to spend it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)